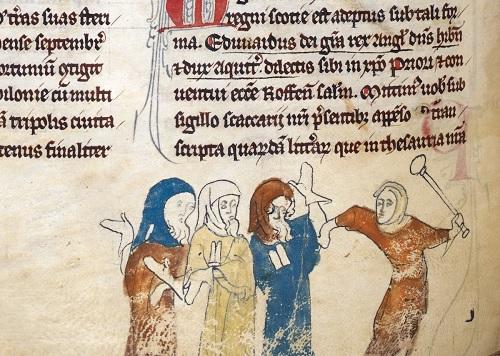

On July 18, 1290, King Edward I signed a decree that would remove every Jew from the Kingdom of England. It became known as the Edict of Expulsion. No other European state had yet taken such a step on a permanent basis.

The timing was intentional. Edward chose the ninth day of the Jewish month of Av, a day of mourning in Jewish tradition. It marks the destruction of Jerusalem and other tragedies in Jewish history.

Edward issued instructions to sheriffs across England. Every Jew had to be out of the kingdom before All Saints’ Day, November 1st.

They were allowed to take money and personal belongings with them. But their homes, businesses, synagogues, and cemeteries became the property of the Crown. Debts owed to them were canceled. Their departure came at great cost.

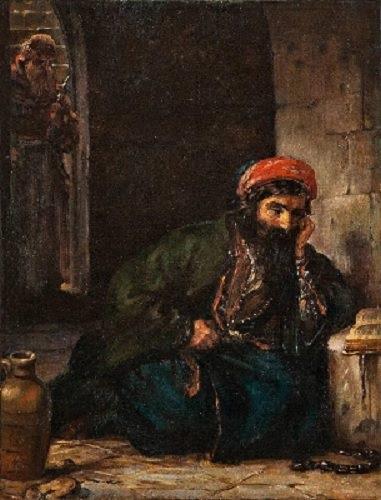

The journey itself was not always safe. Though there were no reports of violence on land, pirates attacked some ships. Others were lost in the Channel, as Jews were forced to travel during a stormy season.

Some survivors made it to France, including Paris. Others found new homes in Spain, Italy, and parts of Germany. Documents carried by these refugees have even been discovered in Cairo.

Back in England, the king and his allies divided up the properties. Queen Eleanor received some of the confiscated land. So did courtiers and royal favorites.

This edict didn’t come out of nowhere. For years, antisemitism had been growing in England. Under Henry III and Edward I, hostility toward Jews became a political weapon. Edward used the expulsion to boost his image—as a defender of Christianity.

After his death, Edward was celebrated for what he had done. The expulsion helped plant the idea that England was “pure”—free of Jews—and closer to God because of it. This belief echoed for centuries.

The ban remained in place until 1656. That year, during the rule of Oliver Cromwell, Jews were quietly allowed to return. It had been more than 365 years since they were forced out.